One of the things that people have noticed about Sigmas is their observable ocular intensity. For example, when I’m not being careful to veil my eyes, it tends to take people by surprise; it’s not at all uncommon for people to physically recoil and even apologize when they meet my gaze. I don’t know why they react this way, but on the few occasions that I’ve asked, they have described the experience as being intense and uncomfortable.

So it was interesting to observe how often Walter Isaacson, in his biography of Steve Jobs, repeatedly refers to the intensity of his eyes and the inability of other people to hold his gaze.

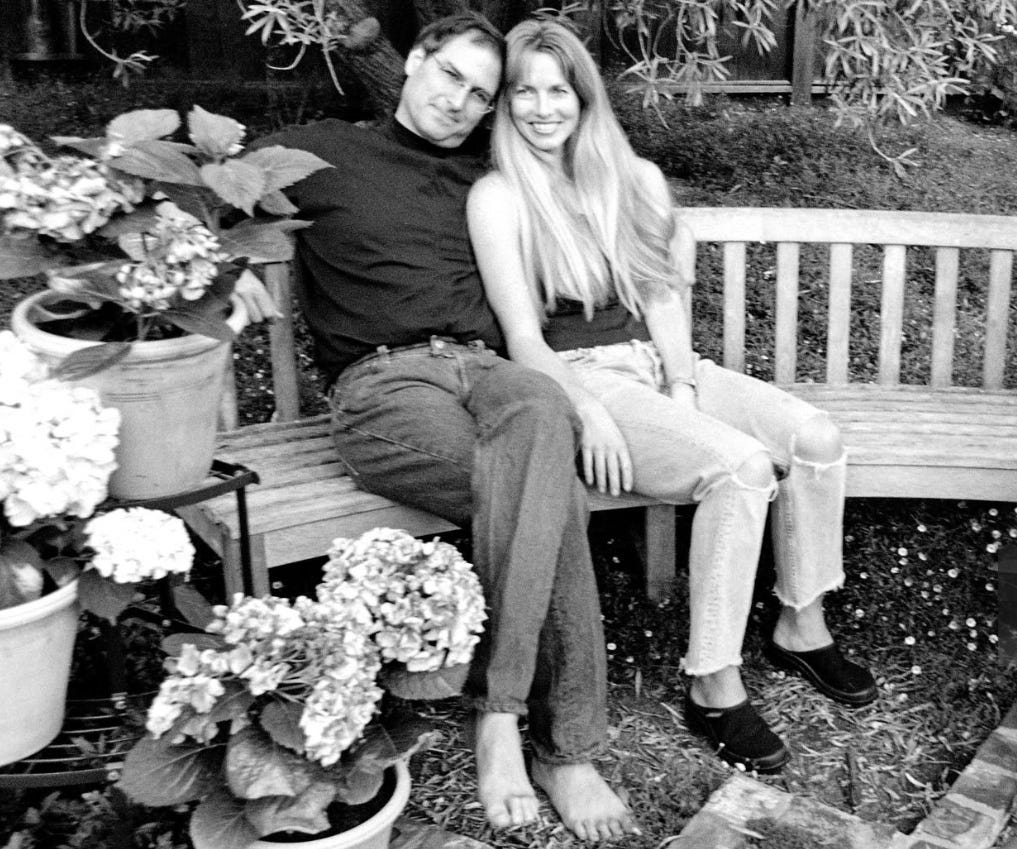

He learned to stare at people without blinking, and he perfected long silences punctuated by staccato bursts of fast talking. This odd mix of intensity and aloofness, combined with his shoulder-length hair and scraggly beard, gave him the aura of a crazed shaman. He oscillated between charismatic and creepy. “He shuffled around and looked half-mad,” recalled Brennan. “He had a lot of angst. It was like a big darkness around him.”

Friedland found Jobs fascinating as well. “He was always walking around barefoot,” he later told a reporter. “The thing that struck me was his intensity. Whatever he was interested in he would generally carry to an irrational extreme.” Jobs had honed his trick of using stares and silences to master other people. “One of his numbers was to stare at the person he was talking to. He would stare into their fucking eyeballs, ask some question, and would want a response without the other person averting their eyes.”

After a dozen assembled boards had been approved by Wozniak, Jobs drove them over to the Byte Shop. Terrell was a bit taken aback. There was no power supply, case, monitor, or keyboard. He had expected something more finished. But Jobs stared him down, and he agreed to take delivery and pay.

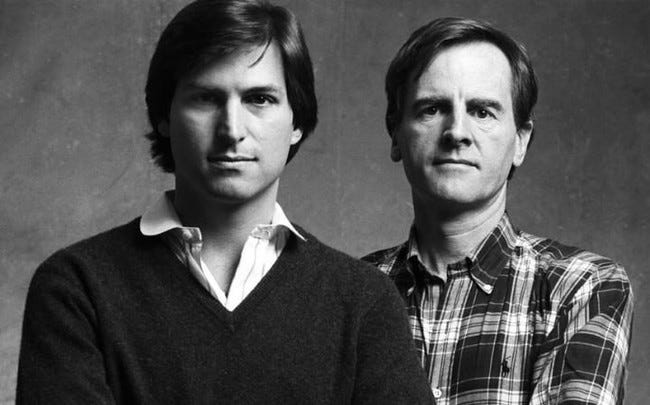

With Apple’s success came fame for its poster boy. Inc. became the first magazine to put him on its cover, in October 1981. “This man has changed business forever,” it proclaimed. It showed Jobs with a neatly trimmed beard and well-styled long hair, wearing blue jeans and a dress shirt with a blazer that was a little too satiny. He was leaning on an Apple II and looking directly into the camera with the mesmerizing stare he had picked up from Robert Friedland.

Time followed in February 1982 with a package on young entrepreneurs. The cover was a painting of Jobs, again with his hypnotic stare.

The consummation occurred outside the penthouse on one of the terraces, with Sculley sticking close to the wall because he was afraid of heights. First they discussed money. “I told him I needed $1 million in salary, $1 million for a sign-up bonus,” said Sculley. Jobs claimed that would be doable. “Even if I have to pay for it out of my own pocket,” he said. “We’ll have to solve those problems, because you’re the best person I’ve ever met. I know you’re perfect for Apple, and Apple deserves the best.” He added that never before had he worked for someone he really respected, but he knew that Sculley was the person who could teach him the most. Jobs gave him his unblinking stare.

Gates was good at computer coding, unlike Jobs, and his mind was more practical, disciplined, and abundant in analytic processing power. Jobs was more intuitive and romantic and had a greater instinct for making technology usable, design delightful, and interfaces friendly. He had a passion for perfection, which made him fiercely demanding, and he managed by charisma and scattershot intensity. Gates was more methodical; he held tightly scheduled product review meetings where he would cut to the heart of issues with lapidary skill. Both could be rude, but with Gates—who early in his career seemed to have a typical geek’s flirtation with the fringes of the Asperger’s scale—the cutting behavior tended to be less personal, based more on intellectual incisiveness than emotional callousness. Jobs would stare at people with a burning, wounding intensity; Gates sometimes had trouble making eye contact, but he was fundamentally humane.

Jobs jumped from his seat and turned his intense stare on Sculley. “I don’t believe you’re going to do that,” he said. “If you do that, you’re going to destroy the company.”

While Jobs may have learned some of his manipulative tricks from Robert Friedland, I believe Isaacson is incorrect in attributing Jobs’s intense stare to learned behavior, even though it’s clear from the book that Friedland was almost certainly a Sigma as well.

According to Kottke, some of Jobs’s personality traits—including a few that lasted throughout his career—were borrowed from Friedland. “Friedland taught Steve the reality distortion field,” said Kottke. “He was charismatic and a bit of a con man and could bend situations to his very strong will. He was mercurial, sure of himself, a little dictatorial. Steve admired that, and he became more like that after spending time with Robert.”

Jobs also absorbed how Friedland made himself the center of attention. “Robert was very much an outgoing, charismatic guy, a real salesman,” Kottke recalled. “When I first met Steve he was shy and self-effacing, a very private guy. I think Robert taught him a lot about selling, about coming out of his shell, of opening up and taking charge of a situation.” Friedland projected a high-wattage aura. “He would walk into a room and you would instantly notice him. Steve was the absolute opposite when he came to Reed. After he spent time with Robert, some of it started to rub off.”

I think it is much more plausible to suggest that Jobs learned how to make intentional use of an ability he already possessed from Friedland, since based on the timeline, his ocular intensity was something that he was observed to possess even before meeting Friedland in 1973. In fact, it appears that Isaacson failed to note that not only was his stare not something that Steve Jobs picked up from Robert Friedland, but rather, something that Friedland himself noted about Jobs.

“One of his numbers was to stare at the person he was talking to. He would stare into their fucking eyeballs, ask some question, and would want a response without the other person averting their eyes.”

In any event, the more we learn about the behavioral patterns, the more accurately we are able to identify how they apply to various men, both in our personal lives and in a historical context.

The massive falling out between Disney and Pixar in the early 2000s was the direct result of an Alpha vs Sigma conflict.

Michael Eisner was a natural Alpha, a strong athlete, a leader from when he was in summer camp, and had no trouble getting the other boys "to row in the same direction."

Jobs and Eisner's relationship reportedly started out as cordial, but I'm not positive about that. I suspect Eisner was always a bit uncomfortable with Jobs but it was fine so long as Eisner remained in the dominant position.

It went downhill fast when Jobs recovered his position as CEO at Apple. The situation appears to have become intolerable to Eisener when Jobs surpassed him in relevance.

The arresting ocular intensity of the Sigma is something that all will be able to recognize, especially in still photos where the eyes can be closely analyzed. That was something I instantly noticed when I saw the covers of Vox’s “Innocence & Intellect” and “Crisis & Conceit.” It was a static picture on a book cover, but he was still looking directly at me! To the guilty party or the unsuspecting Gamma, a Sigma’s eyes might very well burn a hole though his skull.