A Rose for the Gammas

Tracing the Evolution of SSH in Science Fiction

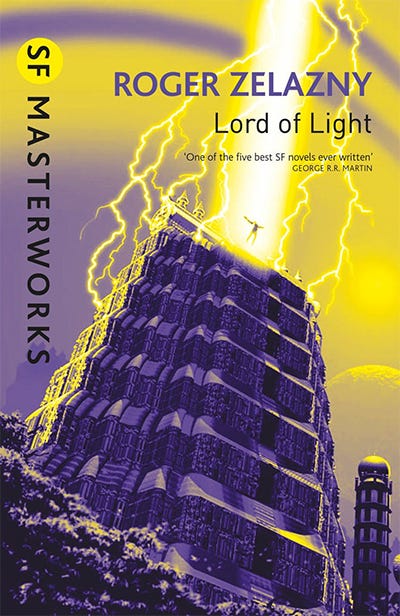

Roger Zelazny is a longtime favorite author of mine. Both his Chronicles of Amber and Night at the Lonesome October have been major influences on my own epic fantasy series, although his best work, and my personal favorite, Lord of Light, is not. But in reading the six-volume set of his collected works, I was somewhat astounded to discover two things. First, I had never read his first major award-winning story, “A Rose for Ecclesiastes”. Second, Zelazny’s story may be the proto-Gamma work that epitomizes the transformation of science fiction and fantasy from a Delta male genre to one dominated by women and Gammas.

“A Rose for Ecclesiastes” was published in 1963, but it was actually written in 1961, prior to Zelazny’s first professionally published work, “Horseman!” a short story published in the August 1962 issue of Fantastic. It is a much-praised short story, indeed, it is considered one of the masterworks of science fiction. Robert Silverberg described it thusly:

No one failed to notice that one. It was nominated for the Hugo award. (The Nebula award had yet to come into existence.) Judith Merril picked it for her Year’s Best Science Fiction collection. And it was chosen, a few years later, as one of the twenty-six great stories included in the first volume of the definitive Science Fiction Writers of America anthology, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, voted by the members of that organization into sixth place on the all-time list. It was the only representative of recent science fiction in a book that was heavily weighted toward the classics of the 1930s and 1940s and included no other story published after 1956. It has been reprinted countless times ever since.

Despite being a moderately serious Zelazny fan, I don’t see it that way. Indeed, quite the opposite. It strikes me as being distinctly inferior to most of Zelazny’s subsequent work, overwrought, overwritten, and rife with needless smartboyisms. But it was certainly influential, as within it can be seen the germ of everything wrong in modern science fiction and fantasy, from John Scalzi’s relentless snarkiness to Patrick Roth’s interminable Special Boy hero-protagonist. In this way, he wasn’t merely one of the leaders of the so-called New Wave in science fiction, he was one of the pioneers of its descent in socio-sexual terms.

Consider the following quotes, all taken from his award-winning 1963 short story.

“You are undoubtably the most antagonistic bastard I’ve ever had to work with!” he bellowed, like a belly-stung buffalo. “Why the hell don’t you act like a human being sometime and surprise everybody? I’m willing to admit you’re smart, maybe even a genius, but—oh, hell!” He made a heaving gesture with both hands and walked back to his chair… “I don’t have to tell you how important this is. Don’t treat them the way you treat us.”

That’s the reason everyone is jealous—why they hate me. I always come through, and I can come through better than anyone else.

I looked at her chocolate-bar eyes and perfect teeth, at her sun-bleached hair, close-cropped to the head (I hate blondes!), and decided that she was in love with me… Did my gaze make her nervous?

Accepting my obeisances, she regarded me as an owl might a rabbit. The lids of those black, black eyes jumped upwards as she discovered my perfect accent. —The tape recorder Betty had carried on her interviews had done its part, and I knew the language reports from the first two expeditions, verbatim. I’m all hell when it comes to picking up accents.

I was six again, learning my Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic. I was ten, sneaking peeks at the Iliad. When Daddy wasn’t spreading hellfire, brimstone, and brotherly love, he was teaching me to dig the Word, like in the original. Lord! There are so many originals and so many words! When I was twelve I started pointing out the little differences between what he was preaching and what I was reading.

I must have been asleep for several hours when Braxa entered my room with a tiny lamp. She dragged me awake by tugging at my pajama sleeve. Her red cloak matched her hair and lips so perfectly, and those lips were trembling.

“Do you want me to dance for you?”

“No,” I said. “Go to bed.”

She smiled, and before I realized it, had unclasped the fold of red at her shoulder.

And everything fell away.

And I swallowed, with some difficulty.

“All right,” she said.

So I kissed her, as the breath of fallen cloth extinguished the lamp.

Little fatty flecks beneath pale eyes, thinning hair, and an Irish nose; a voice a decibel louder than anyone else’s…

His only qualification for leadership!

I stood there, hating him. Claudius! If only this were the fifth act!

“The prophecy is fulfilled,” she said. “My people are rejoicing. You have won, holy man. Now leave us quickly.”

My mind was a deflated balloon. I pumped a little air back into it.

“I’m not a holy man,” I said, “just a second-rate poet with a bad case of hybris.”

I lit my last cigarette.

Finally, “All right, what prophecy?”

“The Promise of Locar,” she replied, as though the explaining were unnecessary, “that a holy man would come from the Heavens to save us in our last hours, if all the dances of Locar were completed. He would defeat the Fist of Malann and bring us life.”

It is our blasphemy which has made us great, and will sustain us, and which the gods secretly admire in us.

It’s all there. I mean, it’s ALL there. Not one single element is missed, from the self-doubting Christ figure right down to the color of the hair of the woman who is inexplicably attracted to the Smart Boy self-insert of the author. That last quote, in fact, praising blasphemy and rejecting the lamentations of Ecclesiastes, is what accounts for the enthusiasm with which Zelazny was greeted by his godless new peers and what helped establish his reputation on the basis of a story that simply doesn’t stand up very well in either a fictional or a scientific sense.

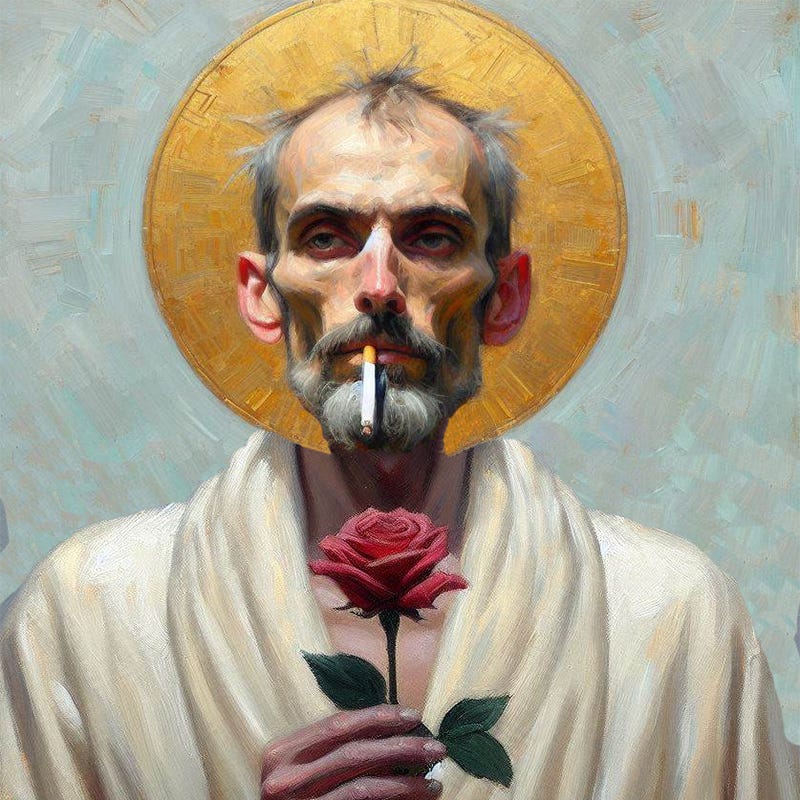

So if you’re ever wondering why science fiction no longer involves science, or engineering, or self-confident heroes rescuing space princesses, if you’re wondering why so little fantasy is even remotely readable anymore, you know who to blame: the patron saint of Gammas in science fiction and fantasy, Roger Zelazny.

Don’t get me wrong. I still love Zelazny’s fiction. But I am grateful that I didn’t read his earlier short fiction until after reading his novels, which are, contra all those reams of praise and early awards, much better than the short fiction that put him on the professional map.

UPDATE: I would have been remiss if I neglected to provide Ecclesiastes’ Epilogue, a poem that was apparently written prior to the story itself, and before the breakup of Zelazny’s engagement to folk singer Hedy West, which inspired the story. But it does indicate, shall we say, a certain mindset.

“As flagrantly

as an old dream is devolved

to nothing,

comes the passing of your desires, woman,

leaving me as one awakened

but not as one refreshed.”

sounds very jewish

I was convinced that when she unclasped her cloak and he swallowed, that we were about to hear bath water being drawn and a tub cuddle was about to commence.